Women Crush Wednesday: Sha-Amun-en-su

This week’s Women Crush Wednesday is a little sad, but I wanted to include her to keep her memory alive. Let’s talk about Sha-Amun-en-su, an Ancient Egyptian mummy lost in the fire at the National Museum of Rio de Janeiro.

Life

Sha-Amun-en-su, meaning “The fertile Fields of Amun,” was an Egyptian priestess and singer who lived in Thebes during the 22nd Dynasty. She was probably born around 800 B.C.E. into a wealthy family. She was probably not born into nobility, but her family was wealthy enough for her to be selected and prepared to work in a temple at an early age.

Sha-Amun-en-su belonged to the main group of priestly singers within the temple complex, called a Heset. They conducted ceremonial duties and ritualistic functions by helping the God’s Wife of Amun. This tradition lasted in Thebes between the 9th and 6th centuries B.C.E.

Interestingly, the Heset were not obliged to live permanently in the temple. Many of them only went to the temple when there were ceremonies. But the women had to obey strict codes of conduct. One of the rules was that they had to stay chaste. They didn’t necessarily have to be virgins, but they were considered extremely pure.

It was also common for an older singer to adopt a younger trainee as their tutor. There is a possibly that Sha-Amun-en-su had an adoptive daughter as there is another sarcophagus in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo for a singer named Merset-Amun. She is labeled as “the daughter of Sha-Amun-en-su, singer of the shrine of Amun.”

She most likely died around the age of 50 years old, but her death could not be determined as her mummy was never unwrapped.

Provenance

There is no record of the date or exact archaeological site where the coffin was found, but it is more than likely from Thebes based on the style of the coffin and that she was a priestess at the Temple of Karnak in Thebes. It originally was in the Egyptian Khedivate collection, which was the rulers of Egypt while it was a vassal state of the Ottoman Empire. In 1876, the Brazilian emperor Dom Pedro II visited Egypt for a second time. Dom Pedro II was an amateur Egyptologist and enthusiast. Khedive Ismail Pasha gifted the sarcophagus and the mummy to the emperor, who in return gave him a book.

The mummy was brought back to Rio de Janeiro and was one of the featured items displayed in the Palace of São Cristóvão. The mummy was part of his private collection and on display in his study. At one point, the sarcophagus was damaged by a storm. It was knocked down by the wind and crashed into the one of the windows in his office. It’s left side was broken, but later restored. There was also a rumor that Dom Pedro II would talk to the mummy while in his study alone.

Because of the Proclamation of the Republic in 1889, the mummy became a part of the Egyptian collection at the National Museum of Rio de Janeiro. In 2015, the curator of the Egyptian collection in the National Museum, Antonio Brancaglion Jr. said in regard to the importance and uniqueness of the sarcophagus,

“If you have a mummy, you have a mummy. If you have not, you won’t get one anymore. If we lose it, we will never get anything else remotely similar. We have to keep it to the end.”

This quote is especially sad, considering that the tragic end of the National Museum on September 2nd, 2018, where the entire museum burned. Almost the entire collection of the museum was lost.

Recovery Efforts

After the fire there have been multiple recovery efforts to help re-establish the National Museum. Via Google Arts and Culture, you can do an entire virtual tour of the museum pre-fire, which you can view here.

Over 300 Egyptian related items have been salvaged from the fire. One of them is the heart scarab of Sha-Amun-en-su, which had never been previously seen because the mummy was never unwrapped. It had been picked up on previous CT scans that I’ll talk about below. But here is a 3D scan of the heart scarab!

This artist did a series of photographs and sculptures for an exhibition titled Museum of Ashes, where he took ashes from the National Museum and recreated some of the lost works, including Sha-Amun-en-su. You can read an interview with him here and see the exhibition pieces here.

And finally there had been multiple contests for artists to recreate something that was lost in the fire. Two artists chose to recreate the face of Sha-Amun-en-su. One is by Gislaine Avila, and the other was by user Rodrigo Avila.

Sarcophagus

The sarcophagus of Sha-Amun-en-su is carved in polychrome stuccoed wood. Its decoration had references to the Heliopolitan theology. The head of the sarcophagus has a blue headdress with a yellow vulture headdress and red ribbons. There is then an image of the goddess Nut and a ram-headed bird with wings outstretched. There are also two uraeus serpents with the crowns of Upper and Lower Egypt and the four sons of Horus.

There was also a representation of the singer’s Ba, which was a part of the Egyptian concept of the soul. On the back of the sarcophagus was a djed pillar which was a sign of stability associated with Osiris.

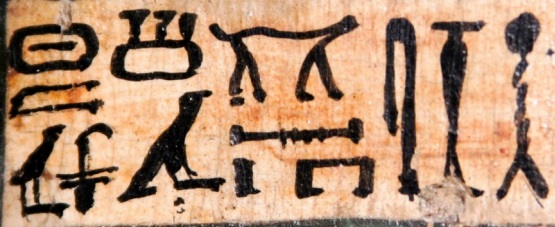

The first band bore the inscription,

“An offering that the king makes [to] Osiris, Chief of the West, great God, Lord of Abydos – made for [?] The Singer of the Shrine [of Ammon], Sha-Amun-en-su “.

And the second line of hieroglyphs reads,

“An offering that the king makes [to] Ptah-Sokar-Osiris, Lord of the [shrine] Shetayet – made for [?] The Singer of the Shrine of Ammon, Sha-Amun-en-su”.[4]

Mummy

Again, all examinations of the mummy have been made without opening the casket as it had never been unwrapped.

The mummy’s throat was covered in resin-coated bandages. This may indicate that the mummifying priests were protecting a zone seen as vital for a singer with ritualistic functions so that she could use her voice in the afterlife. This was also done to a mummy of an singer of Amun at the University of Chicago, Meresamun. This may indicate that this was a special procedure for the mummies of women who were charge of chanting hymns and songs.

The mummy otherwise appears in good condition with no trauma or injuries. Sha-Amun-en-su kept all of her teeth except one. She also went under a 3D laser scan by Jorge Lopes from Tri-dimensional Experimentation Nucleus of the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro. This scan allows for the construction of a small scale replica of her skeleton.

Several amulets were identified in her wrappings. One was the heart scarab that I mentioned previously. It is made out a oval green stone that was previously set in gold (which probably melted in the fire). This was placed on the heart of the mummy so that it could replace her heart which was removed.

Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sha-Amun-en-su

https://mummipedia.fandom.com/wiki/Sha-Amun-em-su

https://www.inprnt.com/gallery/gislaineavila/sha-amun-en-su/

https://www.artstation.com/artwork/v1zLbD

https://anba.com.br/en/brazil-natl-museum-reclaims-its-expertise-in-egyptology/

https://www.zbrushcentral.com/t/sha-amun-en-su-topia-contest/216421

Image Sources

Profile of Mummy – Wikimedia Commons – Gian Cornachini

Mummy – Wikimedia Commons – Dornicke

Inscription of her name and title – Wikimedia Commons – Unknown author

Sarcophagus – Wikimedia Commons – Museu Nacional

X-ray and CT scan, picture of Dom Pedro in Egypt – https://revistapesquisa.fapesp.br/en/emperors-favorite-final-act/

Picture of display – https://english.alarabiya.net/en/life-style/art-and-culture/2018/09/04/Mummy-of-Ancient-Egypt-singer-engulfed-in-Rio-de-Janeiro-museum-fire

Coffin – Wikimedia Commons – Dornicke

Image of fire – https://blog.hmns.org/2018/09/what-the-loss-of-the-museu-nacional-in-rio-de-janeiros-collections-means-to-the-world/

Some of the artifact recovered – https://anba.com.br/en/rio-national-museum-egyptian-items-now-viewable-online/