This week we are going to be looking at an intriguing mummy of an older woman named Nodjmet or Nedjmet found in a cache in Deir el-Bahri. She was definitely a high ranking noble lady married to the High Priest of Amun, Herihor, but she could have also been considered royalty!

Identity Crisis

There is some debate as to if there was only one Queen Nodjmet or two. Some scholars believe that Herihor’s mother may have also been named Nodjmet, and may have been the mummy that we are going to talk about later. This is based on two separate Book of the Dead fragments that were found with the body. She is mentioned as the King’s Mother in both papyri, but never as King’s Wife.

Because of this, some scholars believe that the mummy is of Herihor’s mothers and prefer to call her ‘Nodjmet A,’ and then call the wife of Herihor, ‘Nodjmet B,’ who’s mummy has not been recovered. Unfortunately, there is very little known about the mother of Herihor. She may have been the daughter of Hrere and thus the wife of the High Priest Amenhotep. Read the article below to learn more about this confusion.

The following biography is for the wife of Herihor, who was originally identified as the mummy we’re going to talk about today.

Life of Nodjmet B

She lived in the late 20th to early 21st dynasties in the New Kingdom. She may have been a princess, daughter of the last Ramesside pharaoh, Ramses XI. She was first married to the High Priest of Amun of Thebes, Piankh. He carried the titles of King’s scribe, King’s son of Kush, Overseer of the foreign countries to the South, Overseer of the granaries, and Commander of the archers of the whole of Upper Egypt.

They had at least five children, Heqanefer, Heqamaat, Ankhefenmut, Faienmut (female), and the future High Priest of Amun/Pharaoh Pinedjem I. Interestingly, it appears that Nodjmet was her husband’s most trusted confidant. When he went on a trip to Nubia, it seems that the management of Thebes was under her control. Piankh died around 1070 B.C.E. and his role was replaced by a man named Herihor, who then married Nodjmet.

Herihor is an interesting figure in Egyptian history because he was most likely an Egyptian army official before becoming High Priest of Amun. It is thought that his parents may have been Libyans, but this is not proven. Herihor was also labeled as a vizier under Ramses XI before he seemingly claimed “kingship.”

Though Herihor held the titles of Lord of Two Lands, Son of Ra, Lord of Appearances, and Son of Amun – all of which are typical titles of a pharaoh – he most likely only assumed some royal power after the death of Ramses XI. His kingship was limited to a few relatively restricted areas of Thebes, around the Temple of Amun at Karnak, as Ramses XI’s name was still used on official documents elsewhere.

Because of this, Nodjmet effectively became a queen! Her name was written in a cartouche and she was given the titles of Lady of the Two Lands and King’s Mother. She ended up outliving her second husband as well, and most likely died during the first few years of the next pharaoh, Smendes.

So, let’s talk about the mummy that was found in Deir el-Bahri cache. Even if we don’t know which Nodjmet we’ll be talking about!

Burial

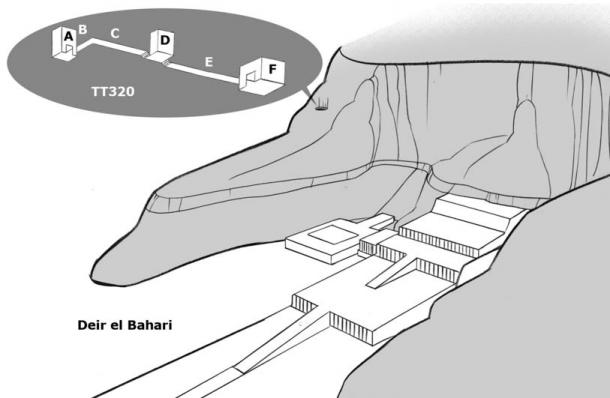

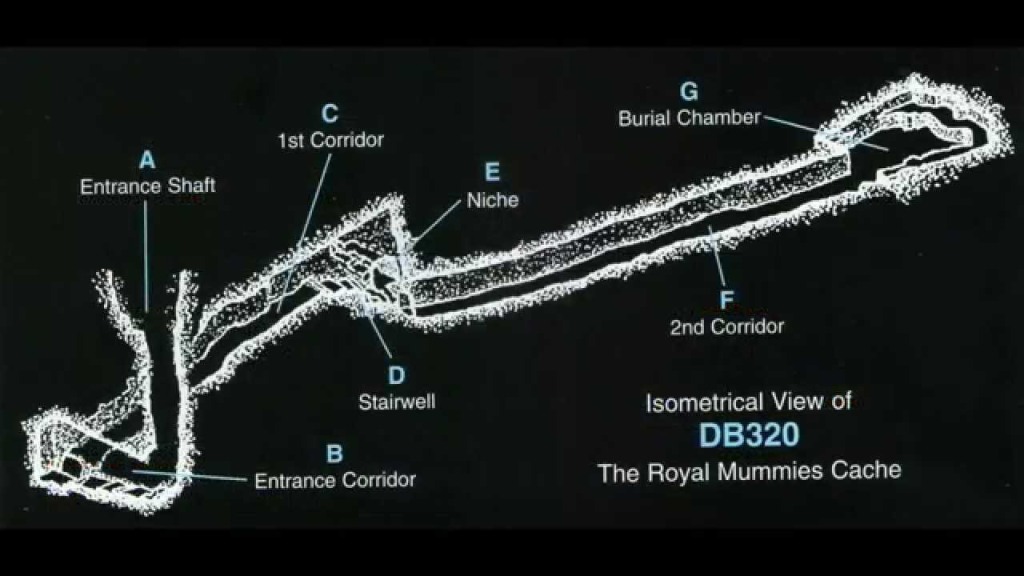

Tomb TT320, previously known as DB320, is known as the Royal Cache. It is located in Deir el-Bahri in the Theban Necropolis, opposite the Nile of Thebes/Luxor. This tomb is also above the famous Middle and New Kingdom funerary temples of Mentuhotep II and Hatshepsut. The tomb was originally intended for another High Priest of Amun, Pinedjem II, and his wife Nesikhons.

Sometime during the 21st dynasty, the tombs of the Theban Necropolis needed a “renewing.” These included the tombs of Ramses I, Seti I, and Ramses II, which had already been looted. These royal mummies were moved multiple times to protect them from looters. The mummies were labeled with dockets stating when they were moved and where they were reburied. When the last of the mummies were placed in TT320, it seems that the opening of the tomb was naturally covered with sand and possibly other debris.

Here is a list of those who were buried in the tomb:

- Tetisheri

- Seqenenre Tao

- Ahmose-Inhapi

- Ahmose-Henutemipet

- Ahmose-Henuttamehu

- Ahmose-Meritamon

- Ahmose-Sipair

- Ahmose-Sitkamose

- Ahmose I

- Ahmose-Nefertari

- Rai

- Siamun

- Ahmose-Sitamun

- Amenhotep I

- Thutmose I

- Baket (?)

- Thutmose II

- Iset

- Thutmose III

- Unknown man C

- Ramesses I

- Seti I

- Ramesses II

- Ramesses III

- Ramesses IX

- Pinedjem I

- Duathathor-Henuttawy

- Maatkare

- Masaharta

- Tayuheret

- Pinedjem II

- Isetemkheb D

- Neskhons

- Djedptahiufankh

- Nesitanebetashru

- Unknown man E

- 8 other unidentified mummies; funerary remains of Hatshepsut

The tomb was found around 1881, by the Abd el-Rassul and his family. They may have actually discovered it around 1871, but that is unclear. The family plundered this tomb for years and sold many of the items found on the antiquities market in Luxor. Canopic jars and funerary papyrus from this tomb were showing up on the market as early as 1874. The local authorities interrogated and tortured two brothers until they gave up the location of the tomb. Apparently, they discovered the tomb because one of their goats had fallen down the tomb shaft.

Emile Brugsch and Ahmed Kamal were the first Egyptologists to investigate the tomb. All the contents were removed from the tomb within 48 hours. The quick removal protected the contents of the tomb from possible looters, but the archaeologists did not document anything. The locations of the mummies and other contents were never recorded, and even when Brugsch went back, he was not able to document it reliably by memory.

Many of the items were also damaged before and after removal. Fragments of coffins were found in the tomb by later archaeologists, indicating that they were damaged during the quick emptying of the tomb. But ten of the coffins were missing the footends which were not found in the tomb, indicating that they were damaged before placing in the tomb. Obviously, the only reason the mummies were in this tomb was that their original tombs had already been looted, so the bodies are not in great condition. Some of the heads and limbs had been removed to find precious amulets or jewelry that the deceased wore.

Since the excavation in 1881, the near-vertical shaft was left open, which allowed debris and rocks to fill the hole. The tomb was reinvestigated in 1938 and then later in 1998 by a Russian and German team. This team cleared the passageways and were able to find fragments of coffins and other small items. After clearing debris away from the walls, they were also able to find some paintings on the walls, which helped them conclude that the tomb was originally owned by a family from the 21st Dynasty.

Watch this Youtube video or read these articles to learn more about the royal cache!

Coffin and Papyrus Fragments

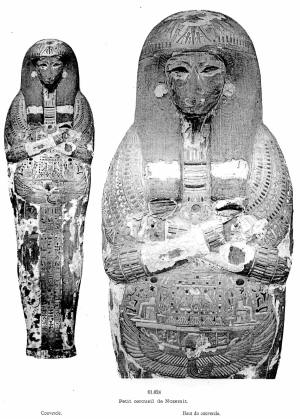

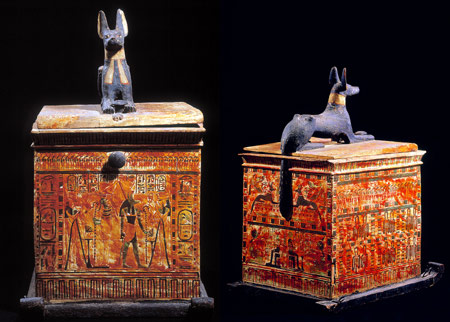

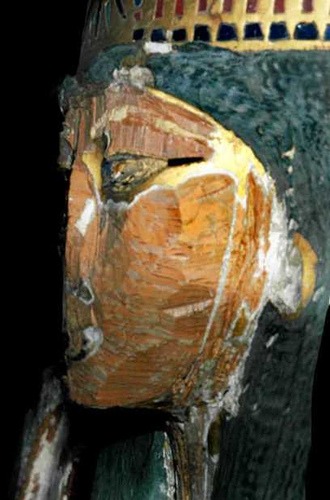

The mummy of Nodjmet was nested in two coffins (CG 61024), made of cedar wood with sycamore wood faces. The coffins had been originally fashioned for an unidentified man and had either been usurped from the original owner or were perhaps donated by him. They probably had the original gender markers commonly used on men’s coffins, such as stripped wigs, face masks depicting ears, and clenched hands. If this was the case, the coffin was probably completely reworked as the ears were replaced with disc-shaped earrings and the wigs represent finely braided hair. The hands were removed sometime in antiquity, but the outlines indicate that they were originally gilded and clenched.

Outer Coffin

Inner Coffin

On both of the coffins, the gliding has been completely adzed off and the eye inlays have been removed. The outer coffin’s surface has been almost completely removed, indicating that it was probably lavishly decorated with a thick gold foil. This was hacked off with an adze, which is an ancient cutting tool similar to an ax, in a very crude and hurried fashion.

But the inner coffin was handled with greater care. The inscriptions and religious symbols remain intact, indicating that the coffins had been stripped by necropolis officials and priests rather than thieves. They probably didn’t want to completely violate the coffin of one of their royal ancestors, so they left the inscriptions intact.

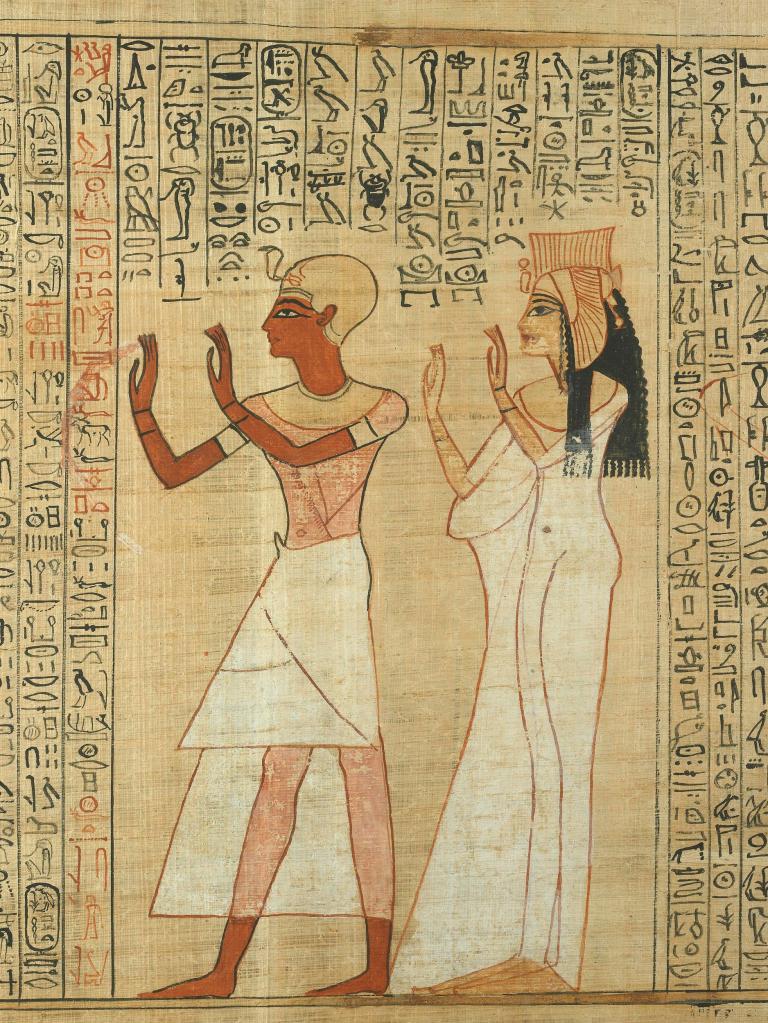

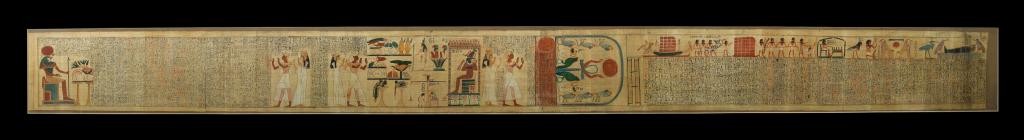

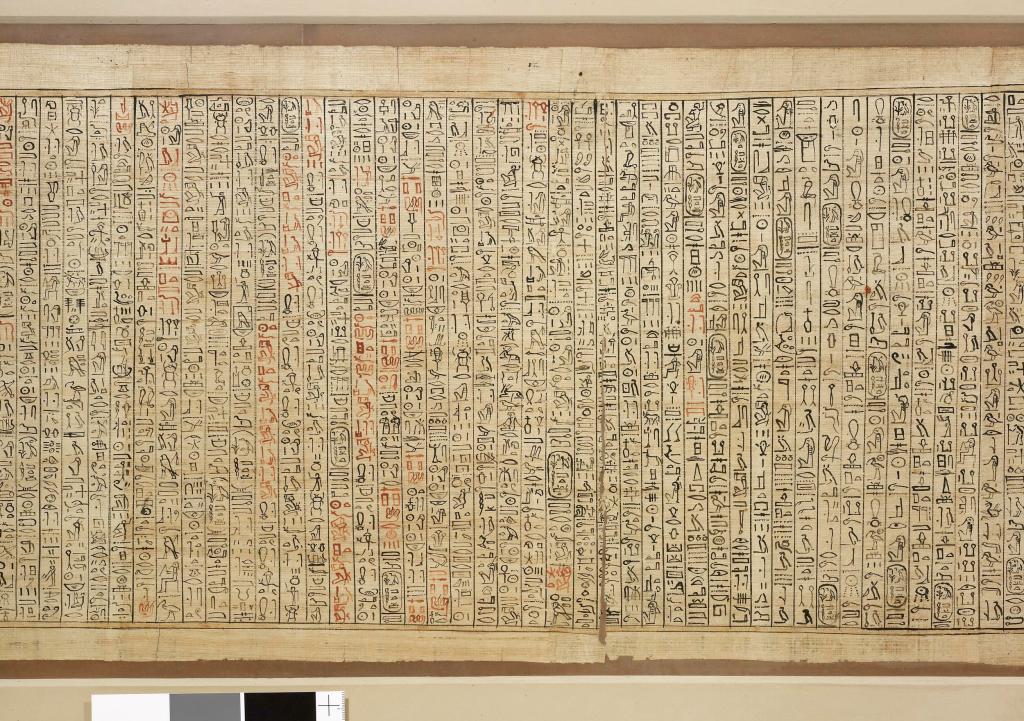

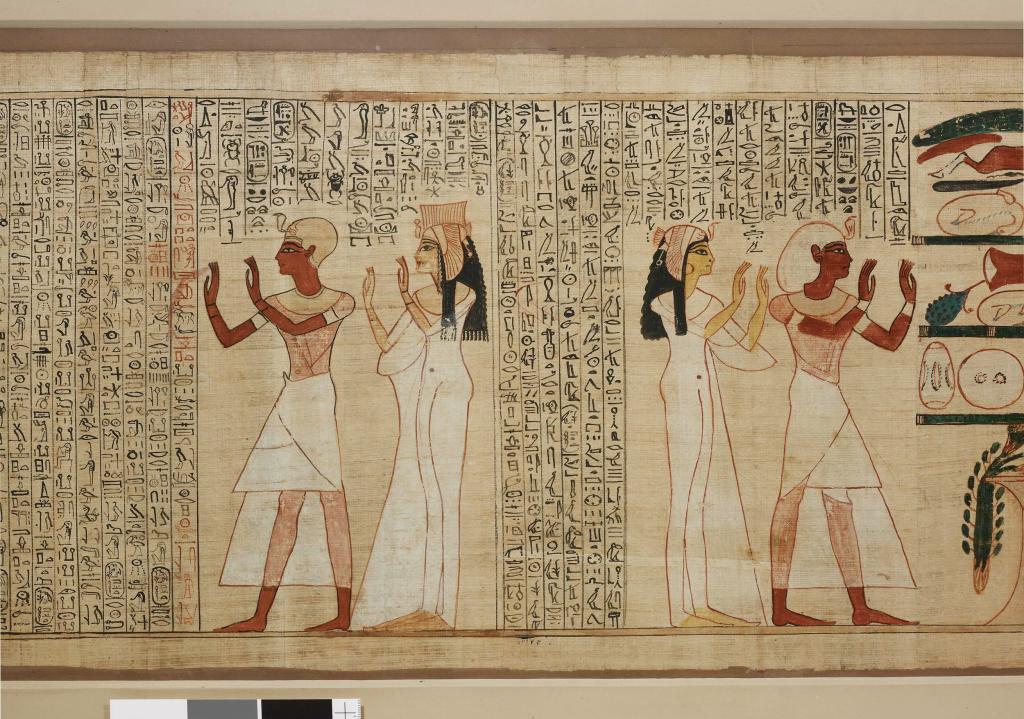

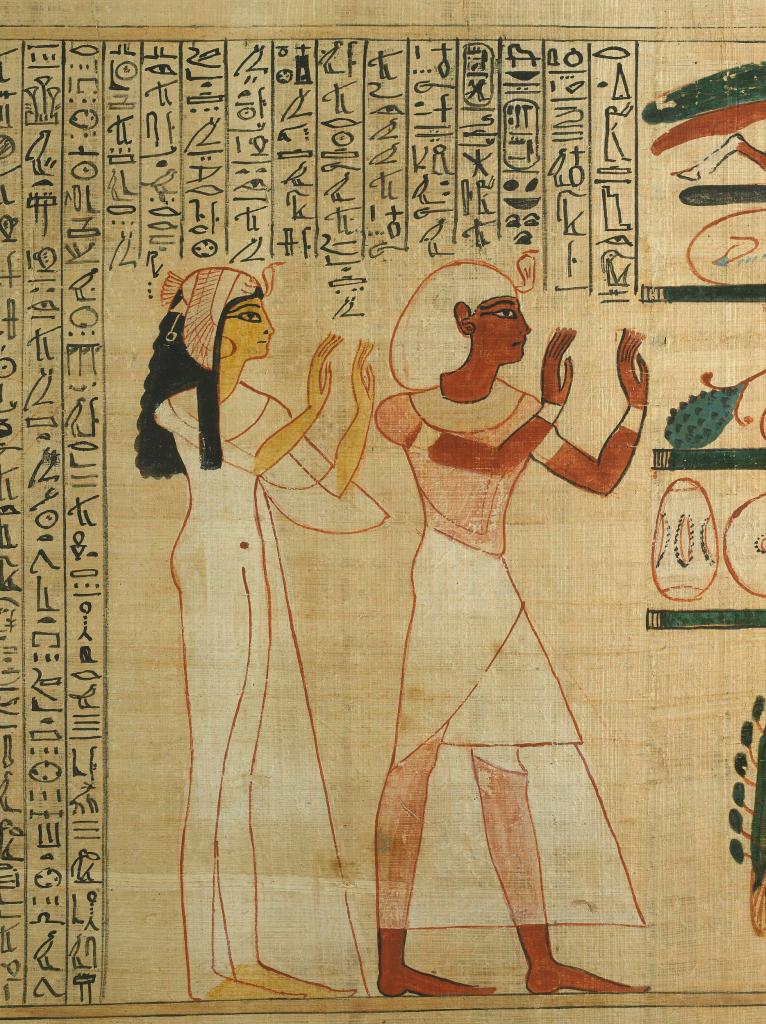

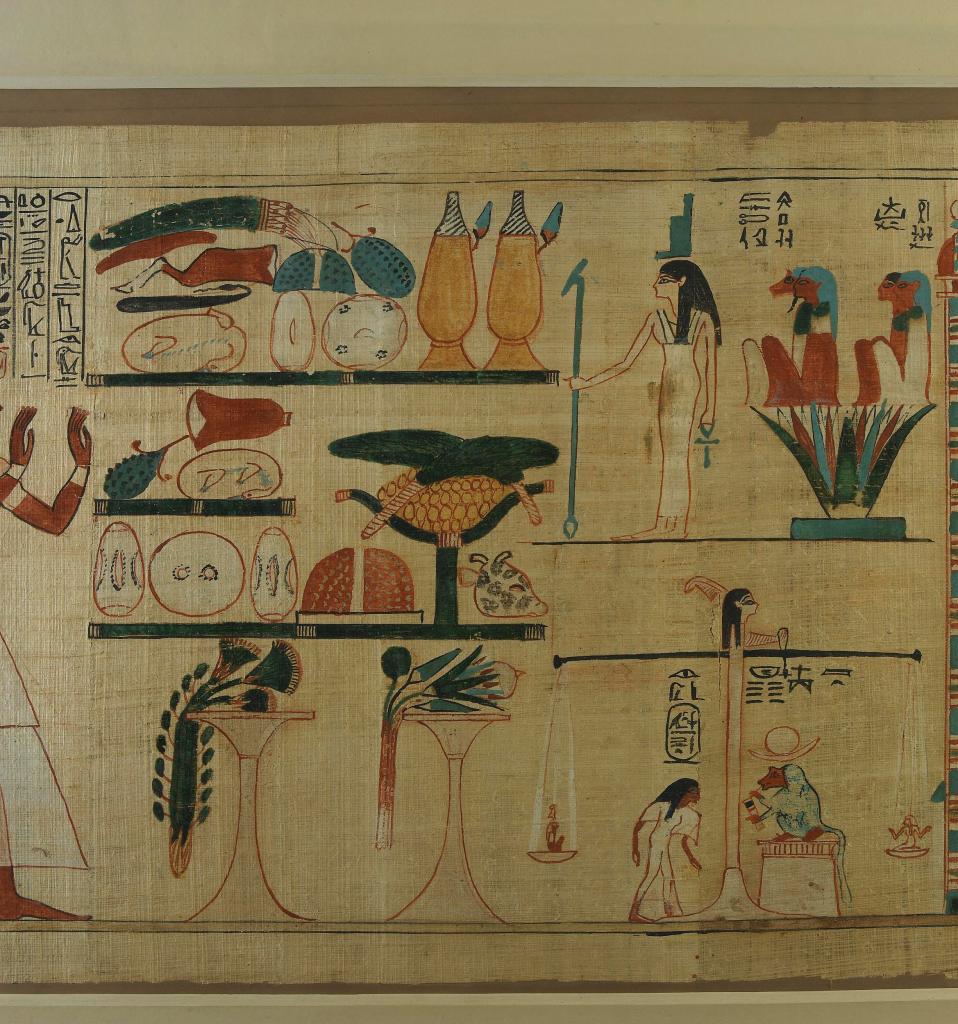

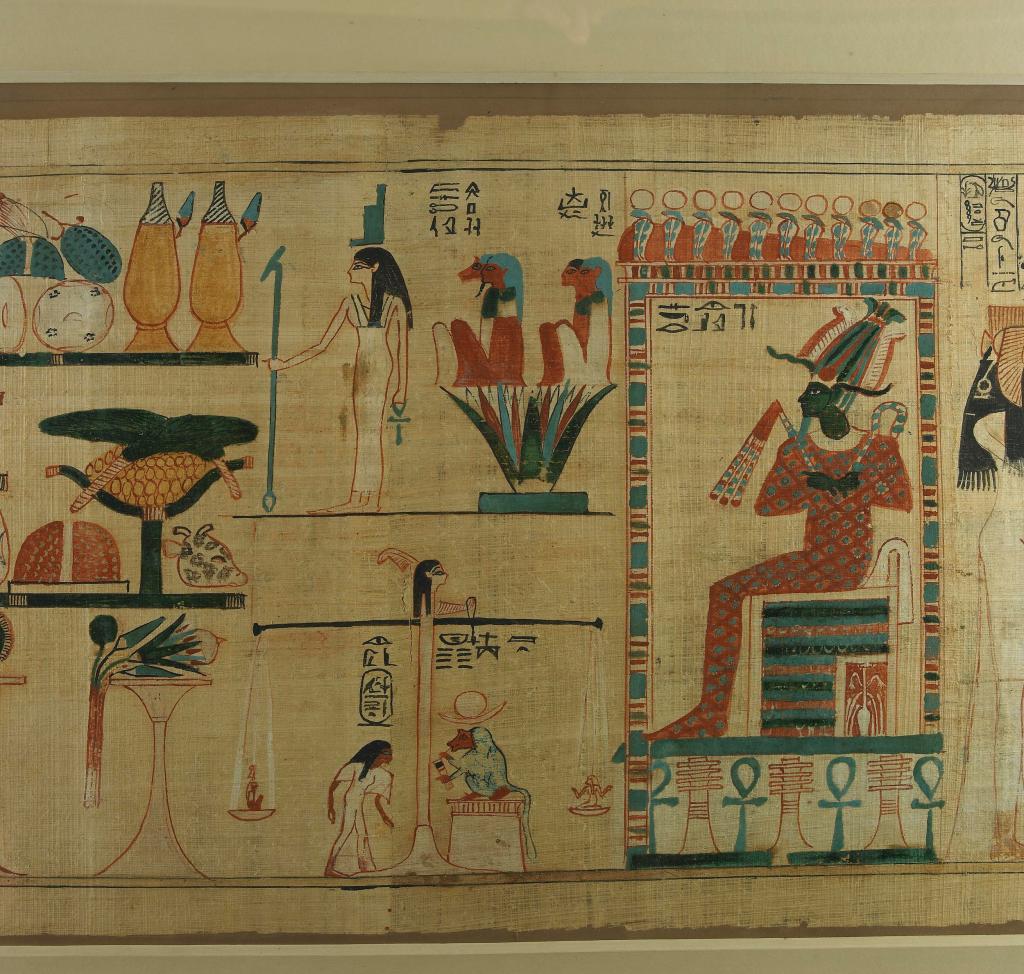

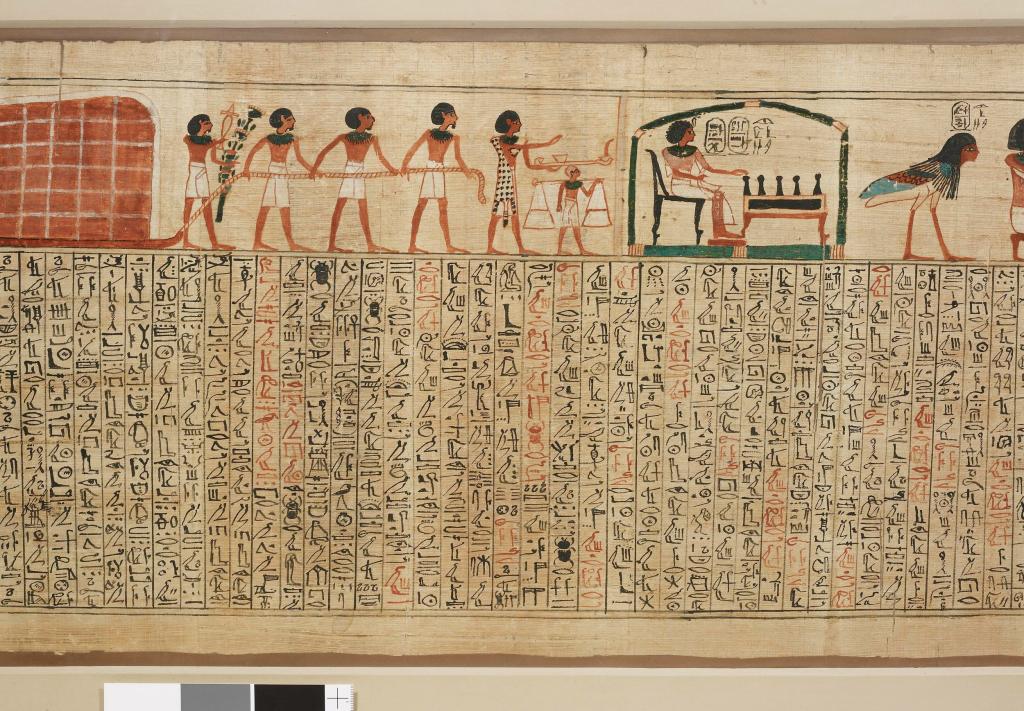

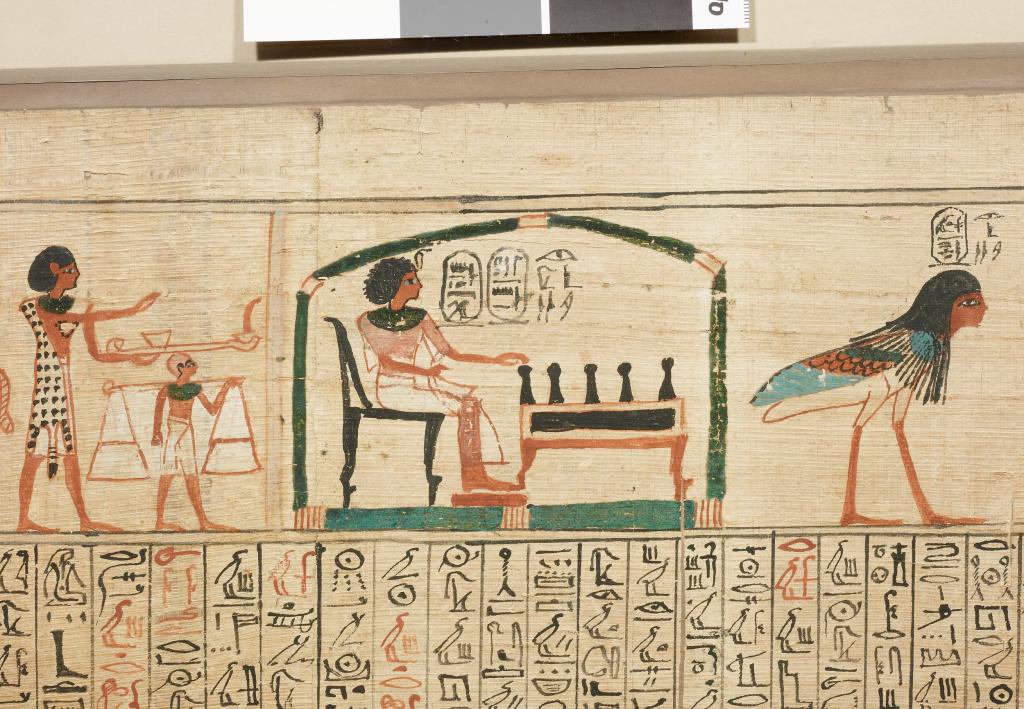

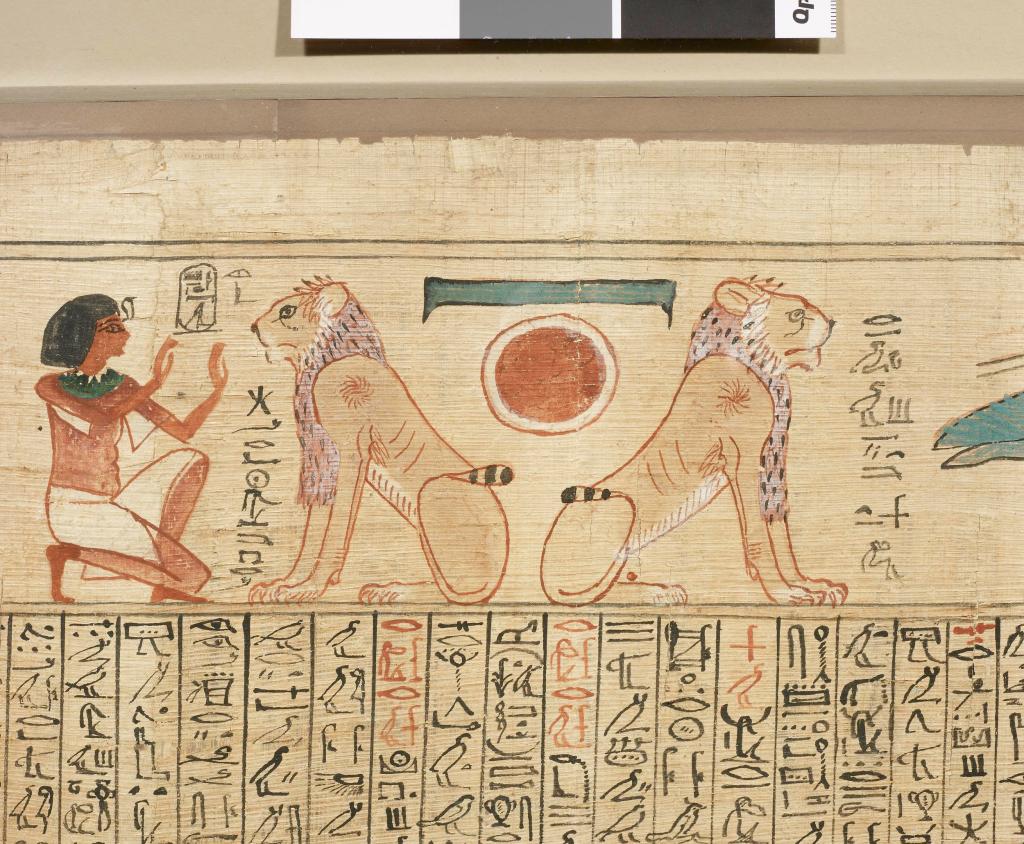

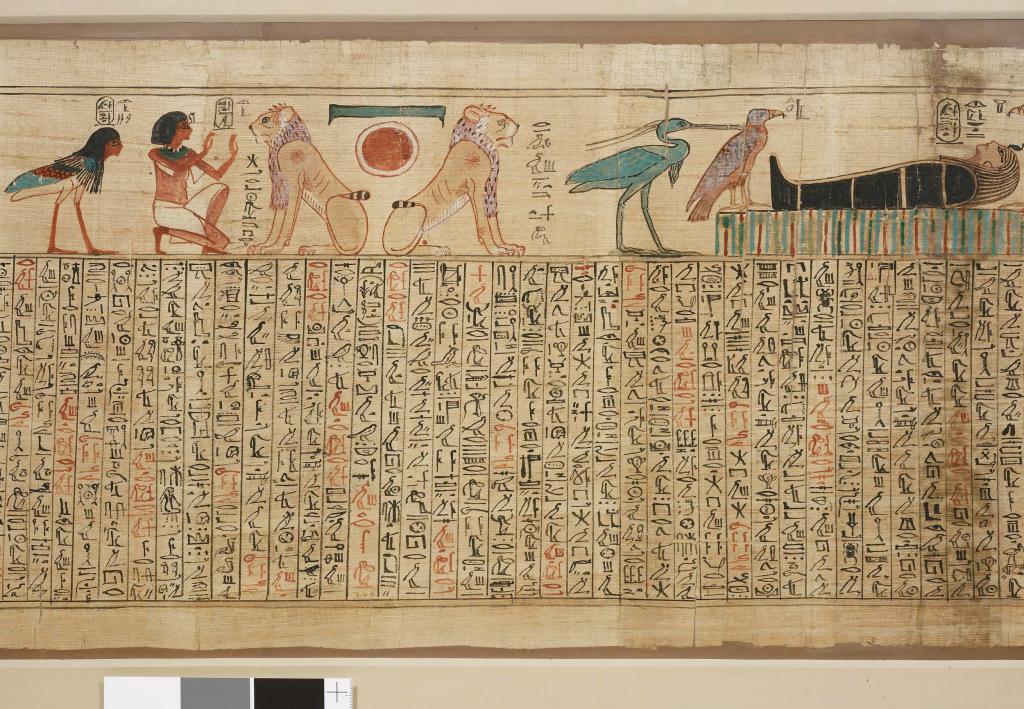

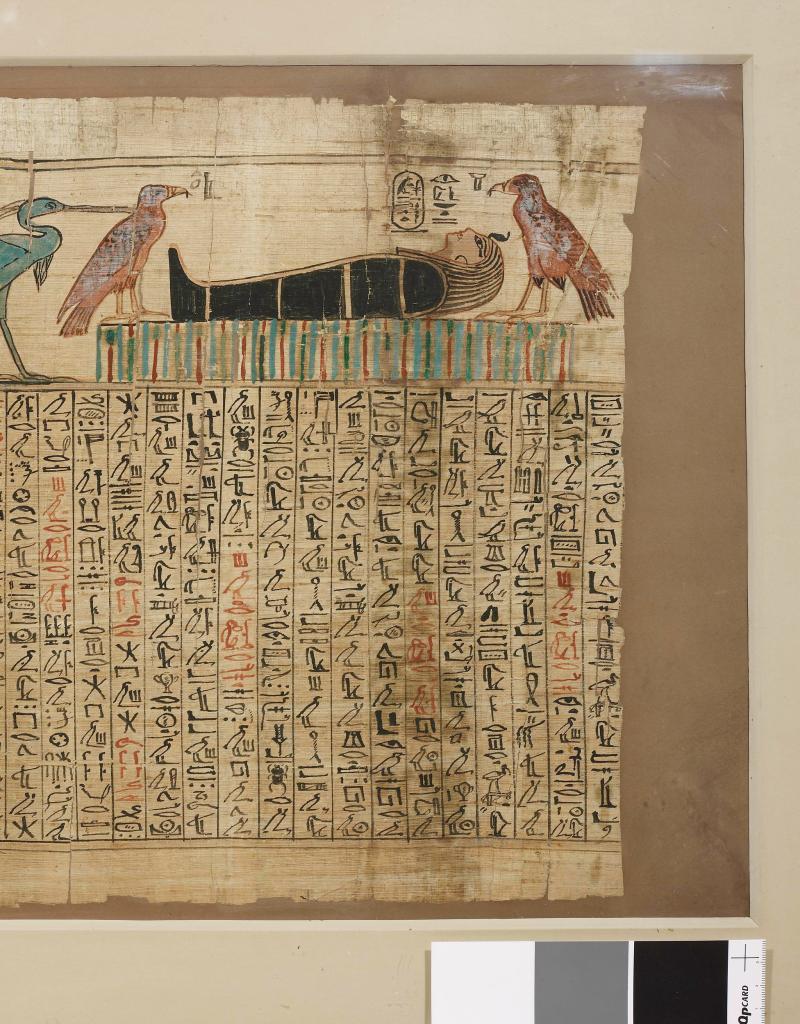

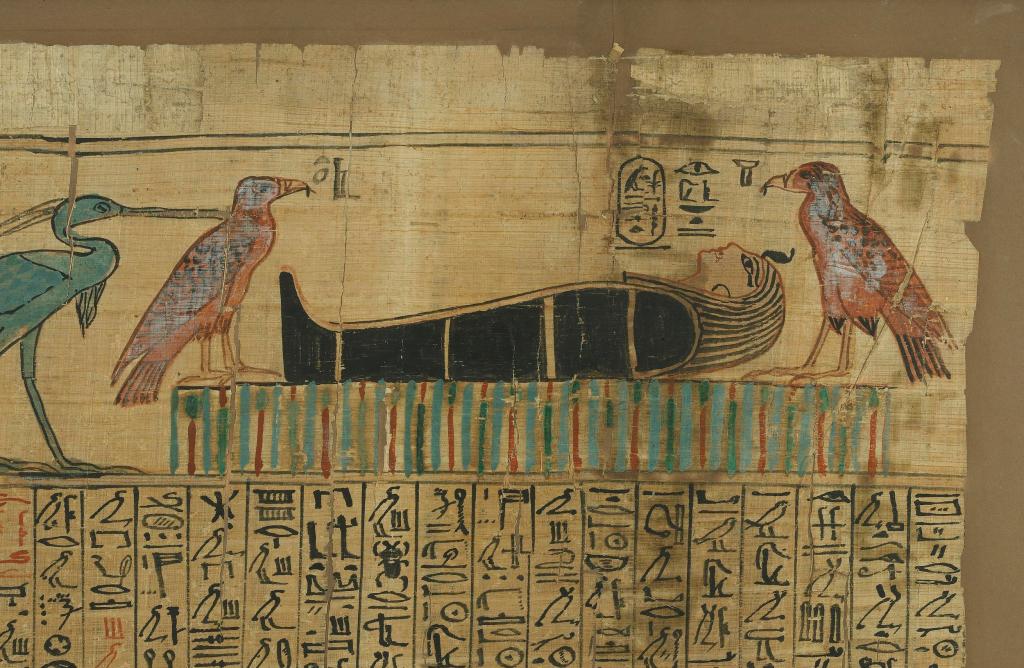

As I said earlier, two separate Books of the Dead were found with the name of Nodjmet. One of these was taken from the tomb by the El-Rassul brothers and sold on the antiquities market. The two pieces are located in the British Museum.

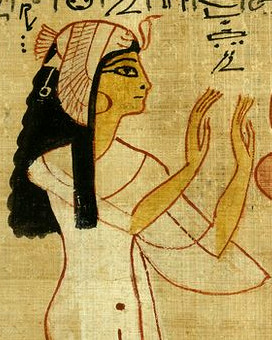

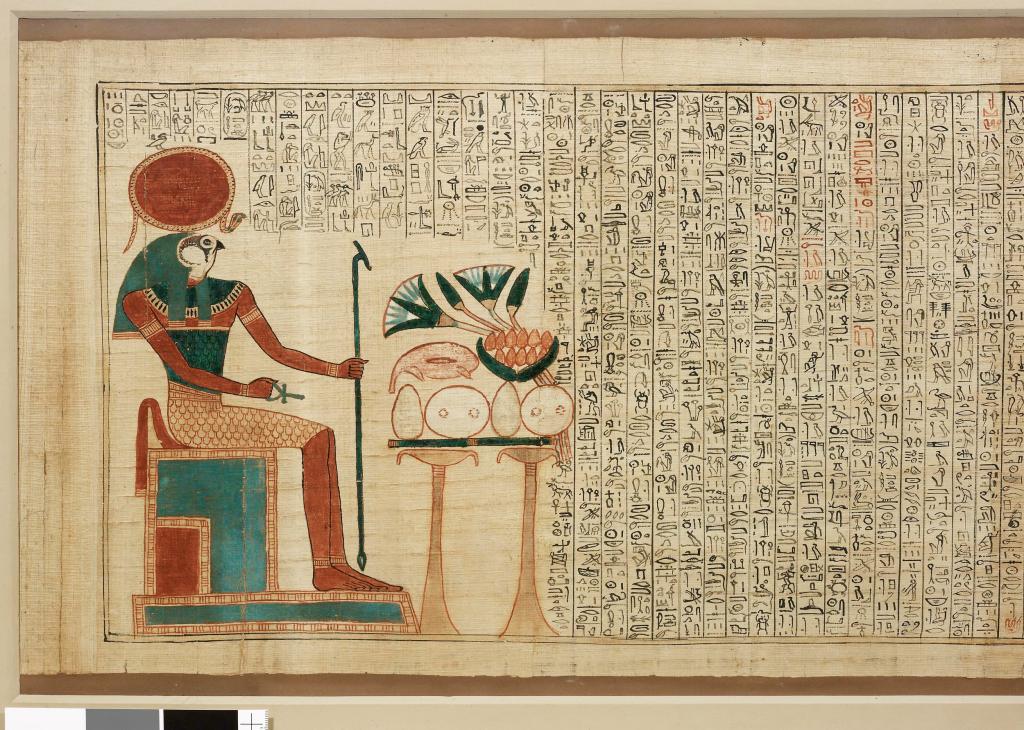

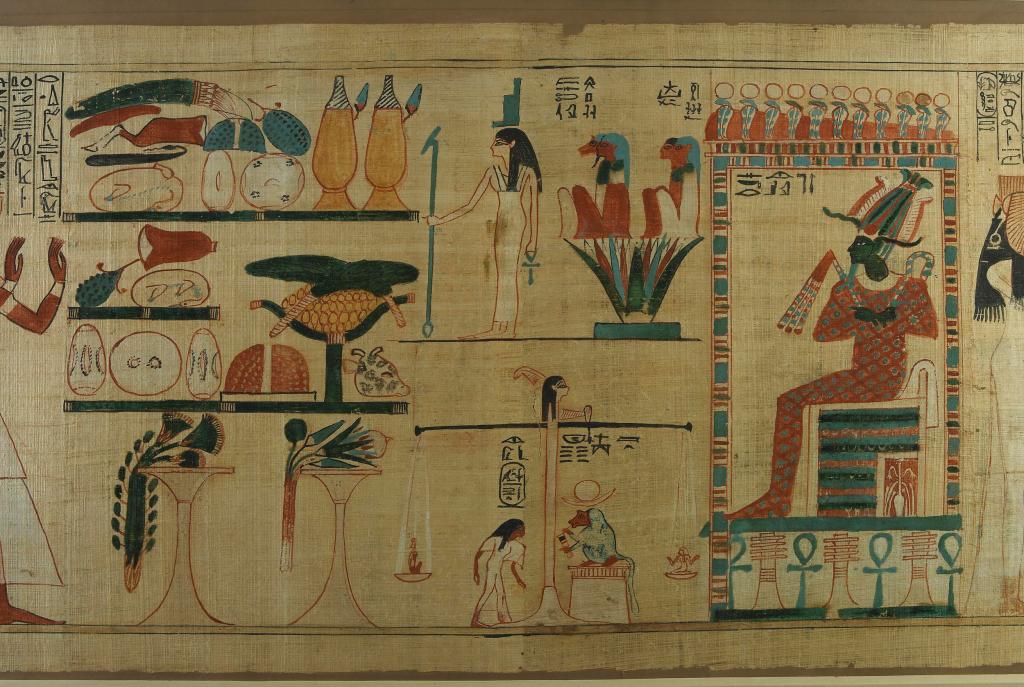

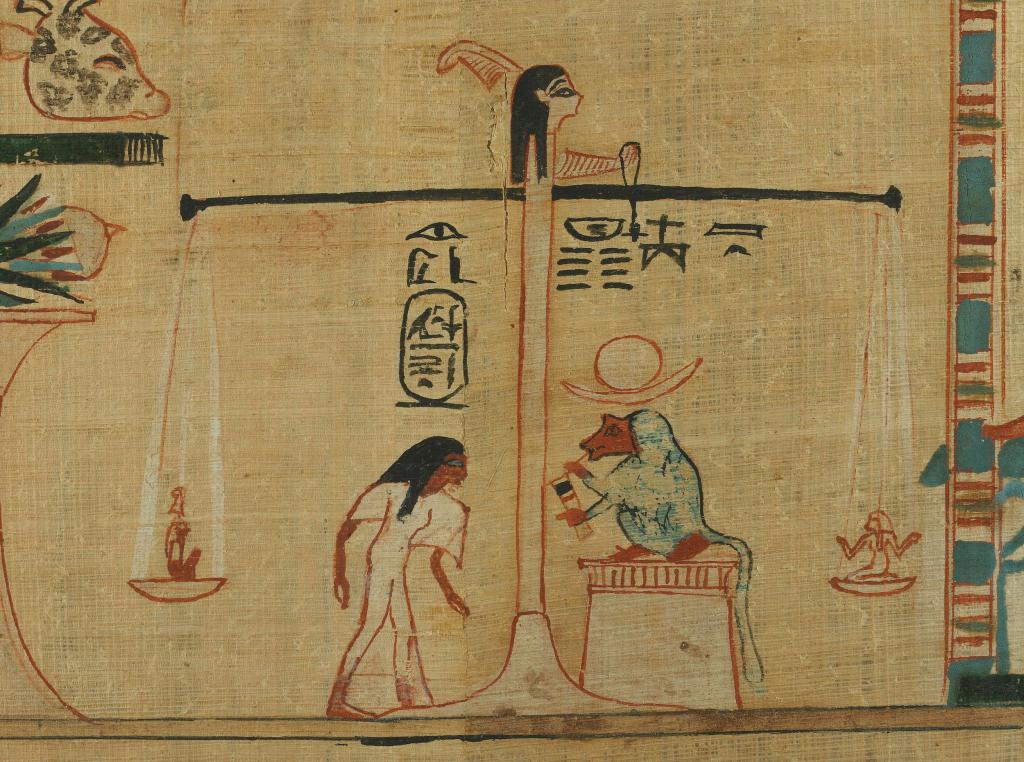

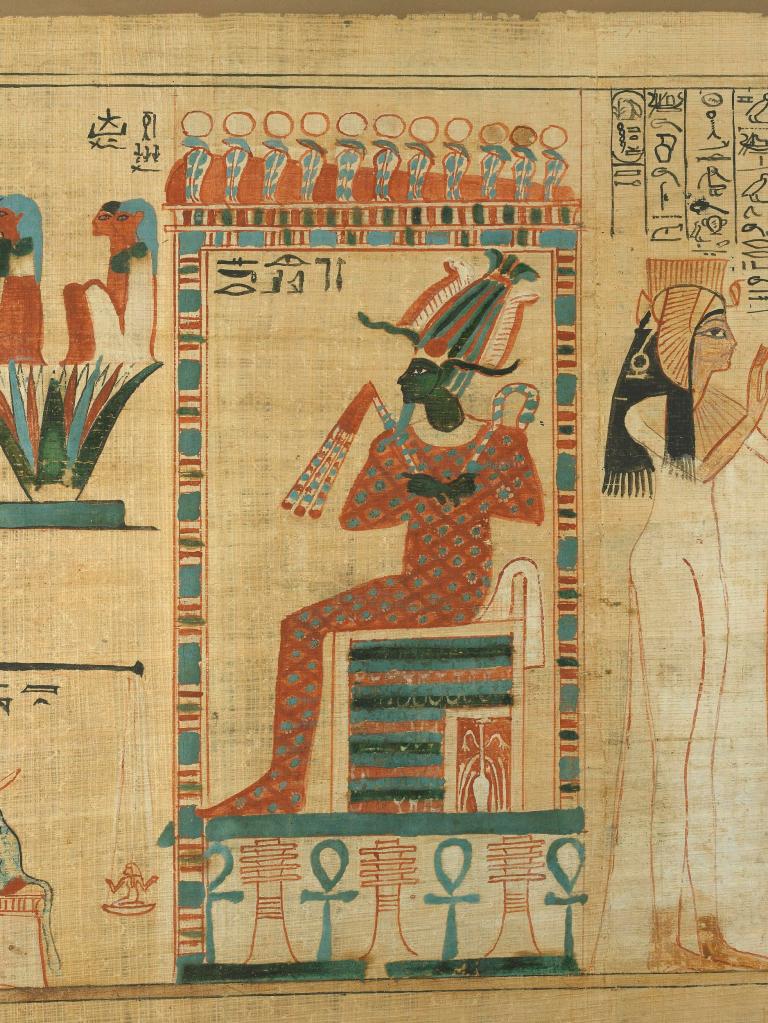

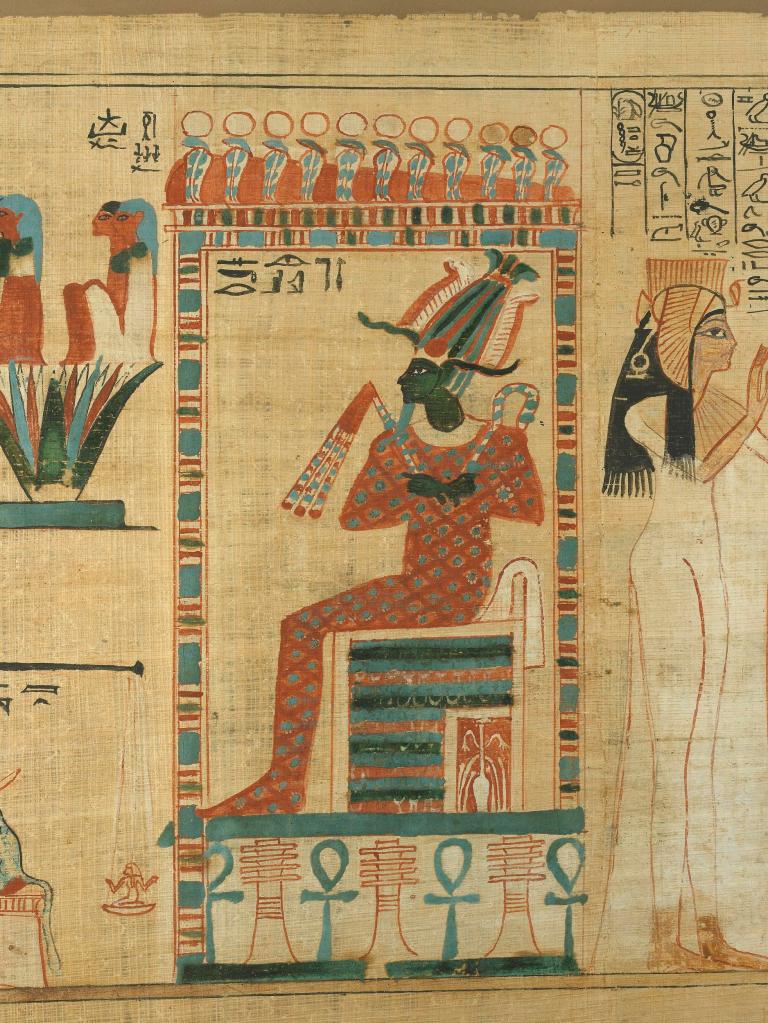

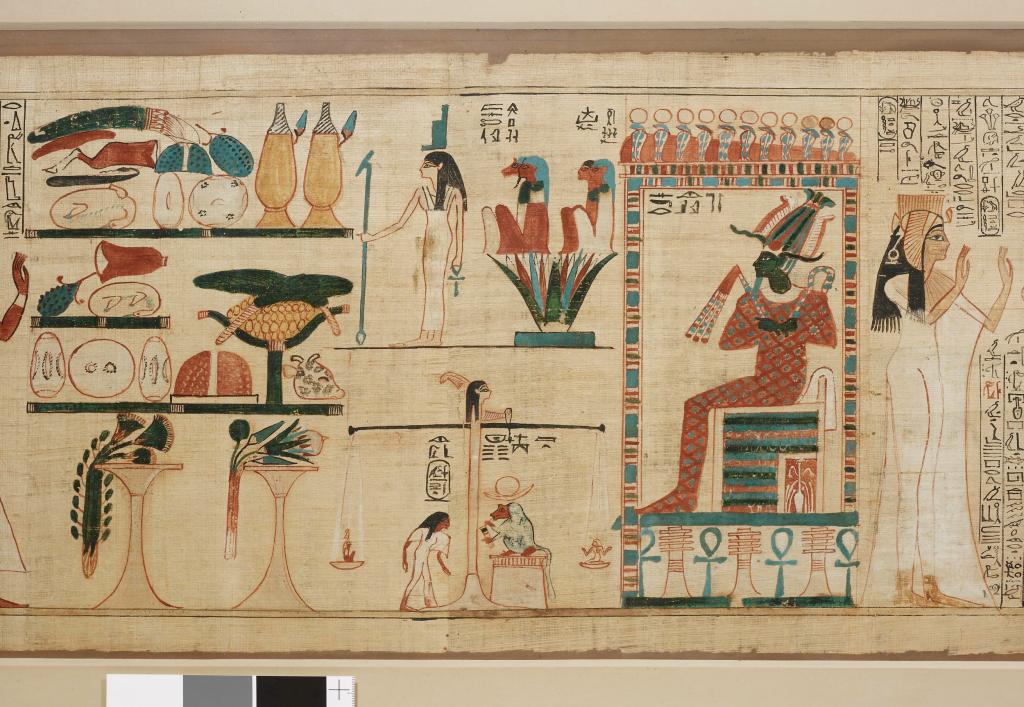

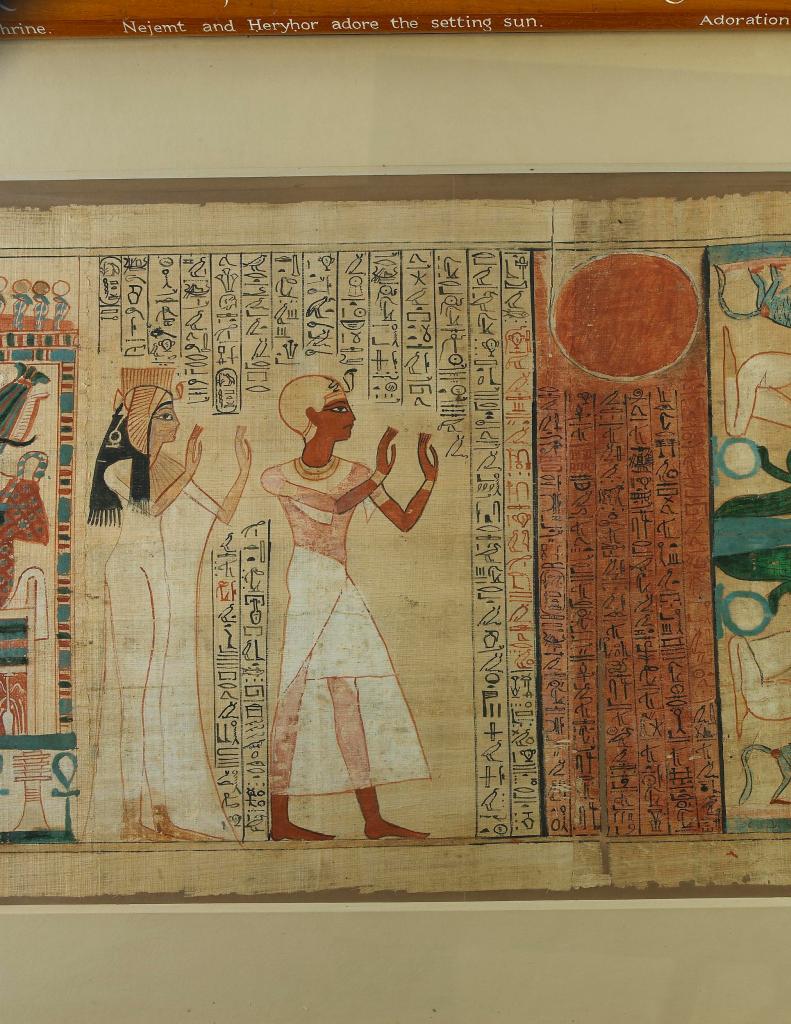

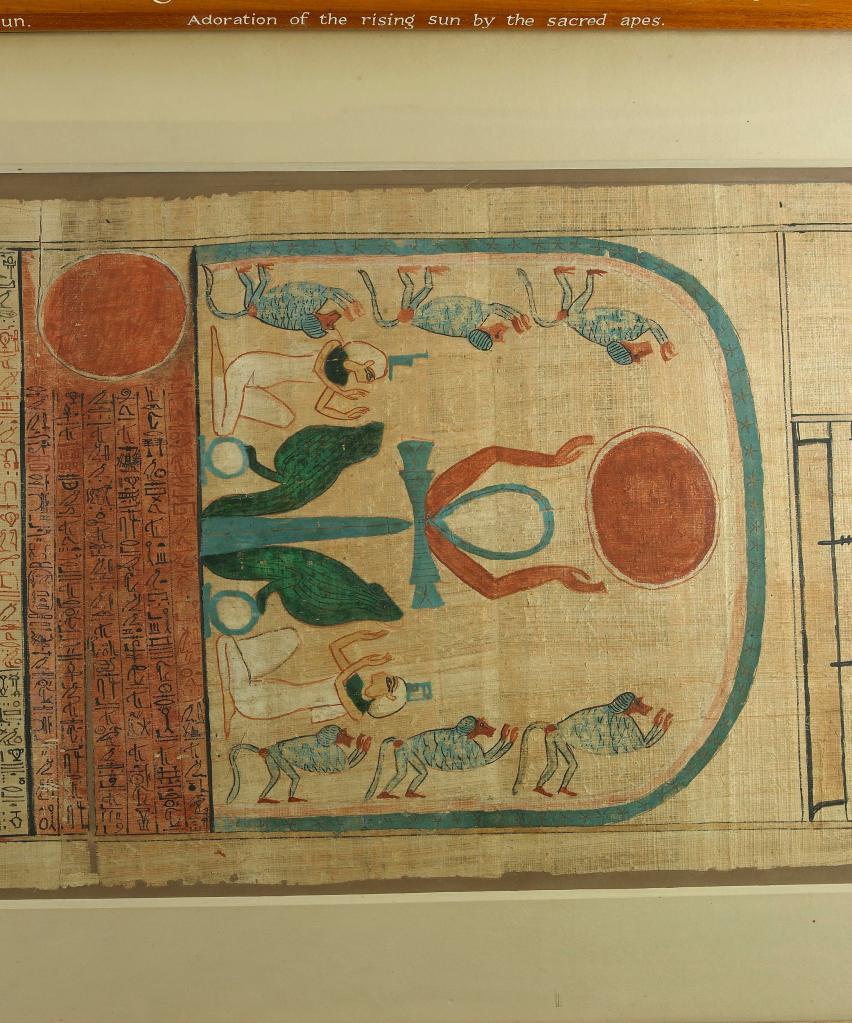

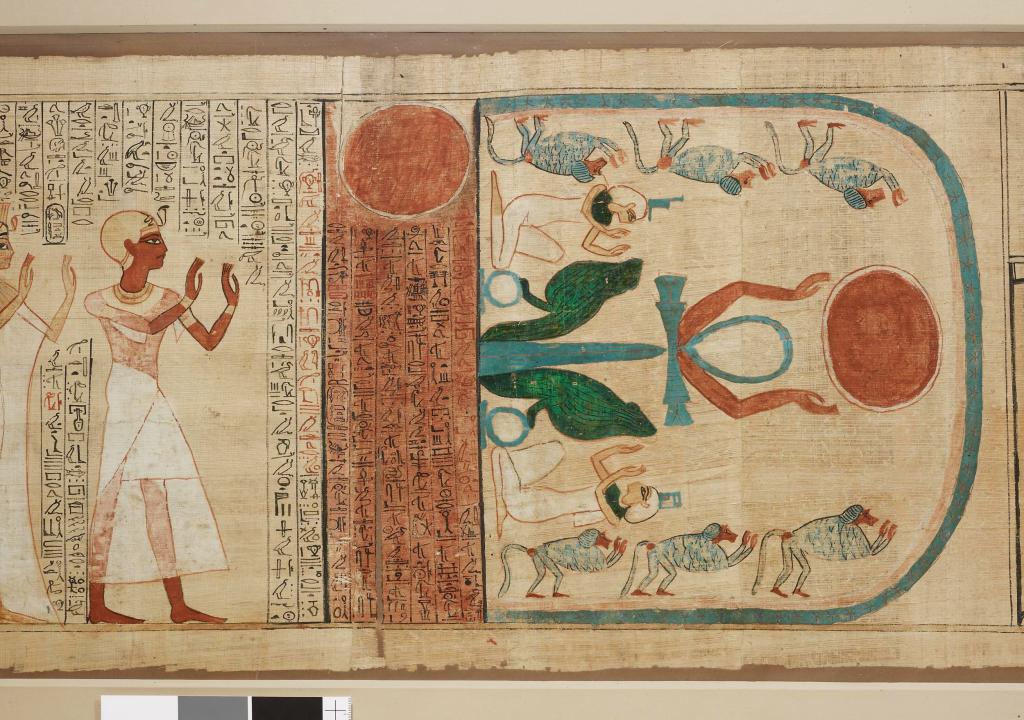

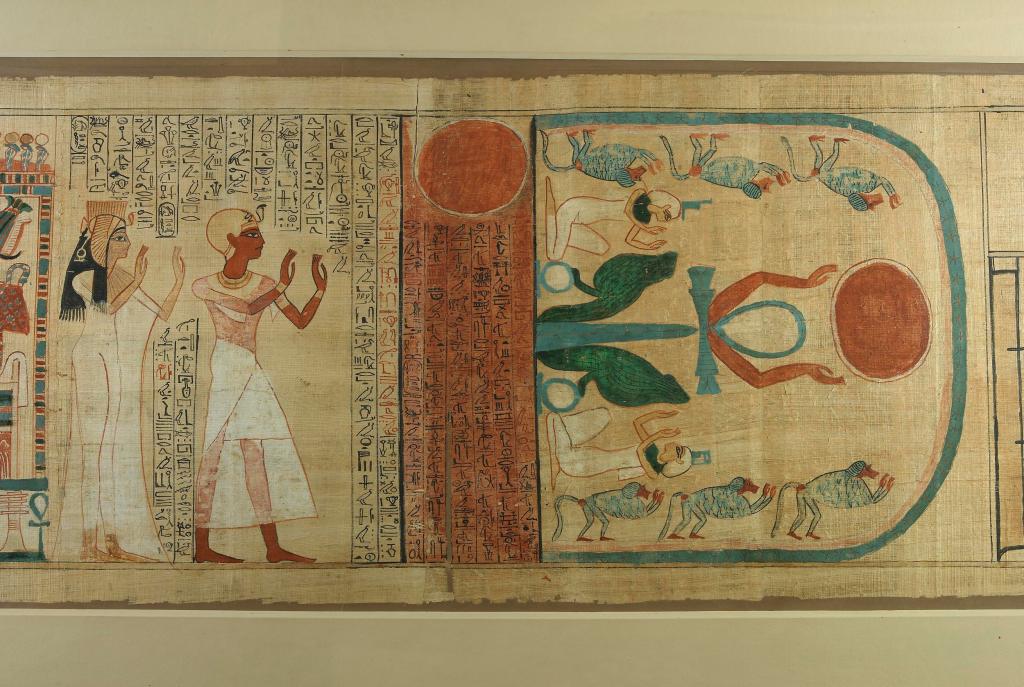

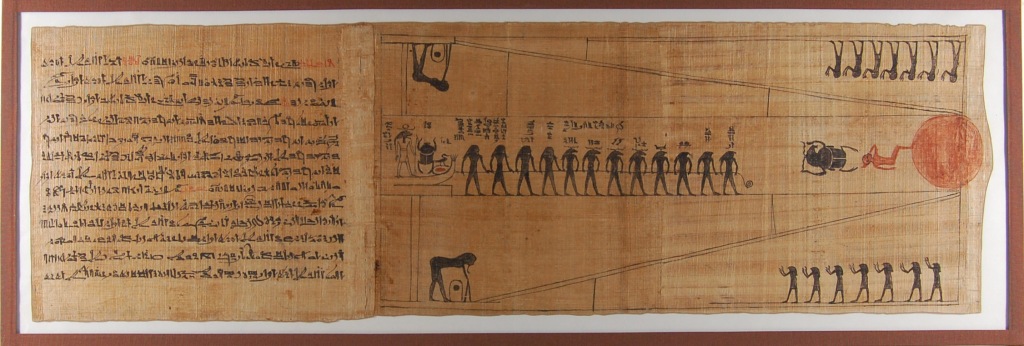

Papyrus EA 10541 is richly decorated with colorful images of Nodjmet, Herihor, and the gods. I one scene, Nodjmet’s heart is being weighed against Maat, the goddess of truth and justice. While this scene is very popular in the New Kingdom, the symbol of the heart is usually used. In this scene, a small figure of a woman is used, presumably to represent Nodjmet. This is supervised by the god Thoth in the form of the baboon.

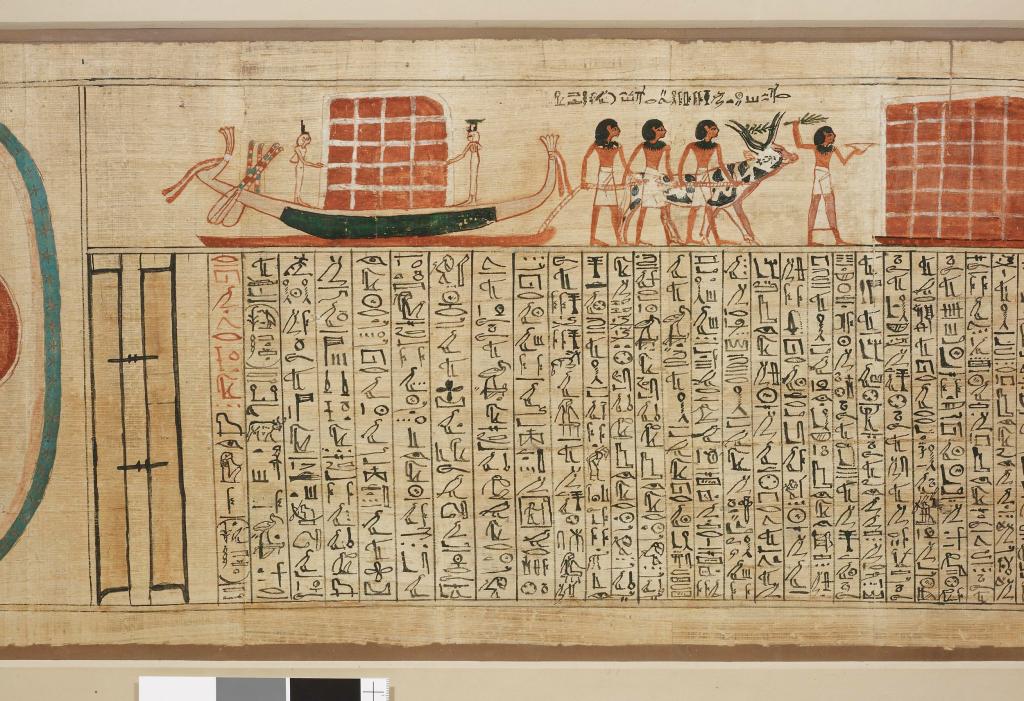

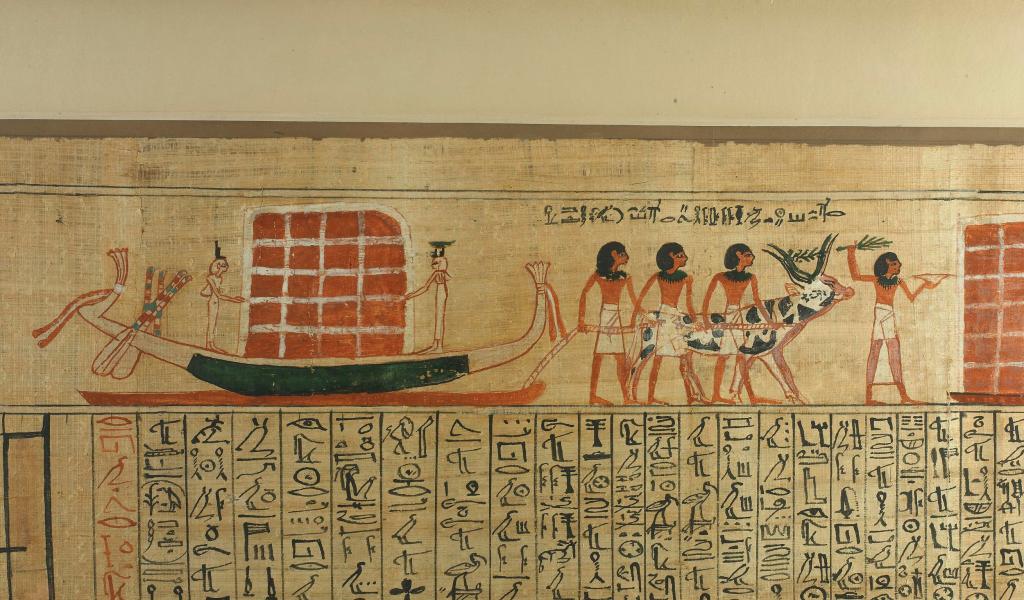

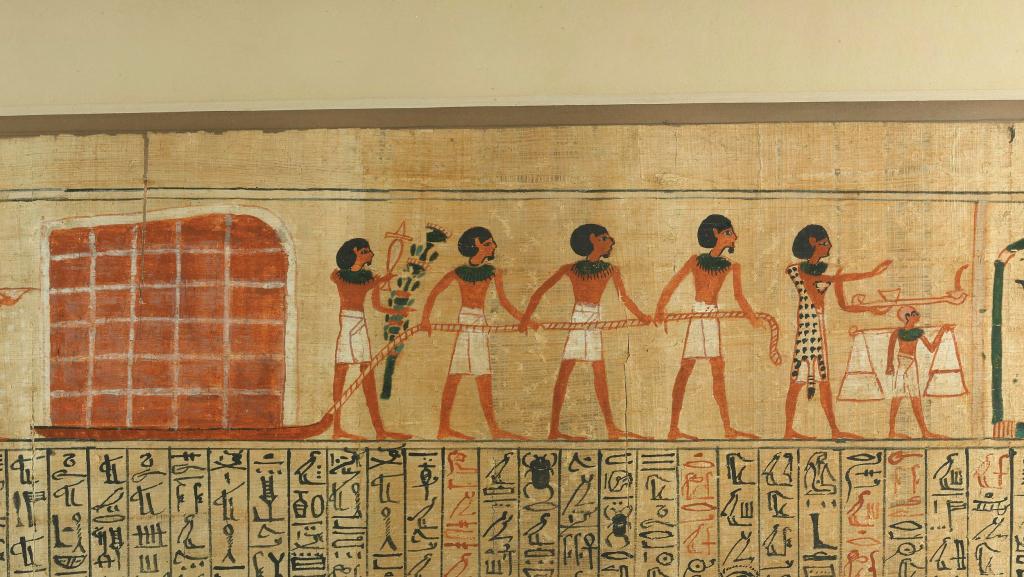

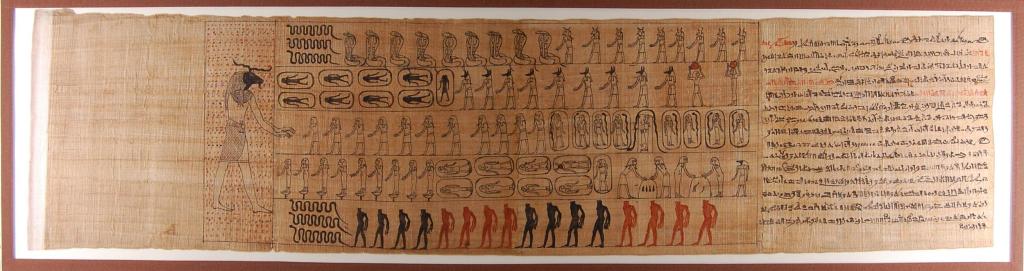

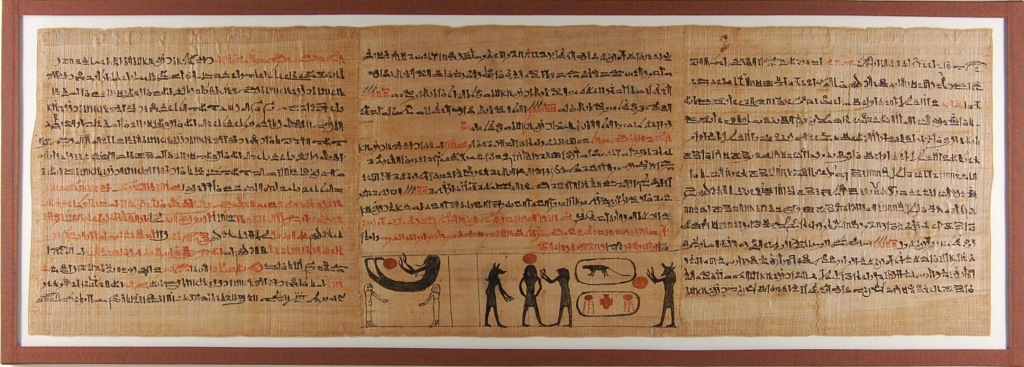

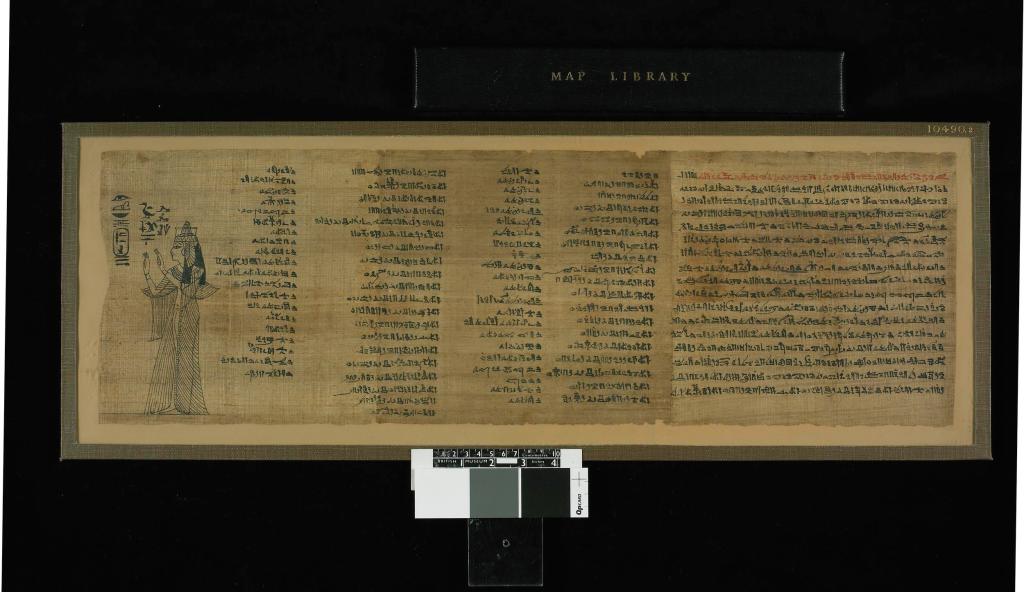

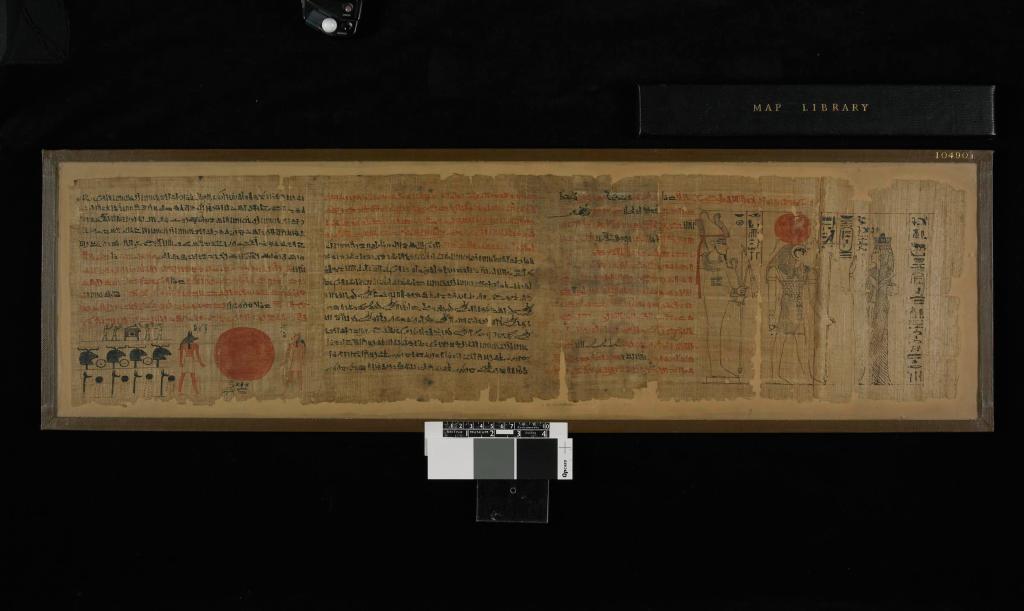

Papyrus EA 10490 is split into five sections. It is not nearly as colorful, but it is still in excellent condition featuring multiple depictions of Nodjmet with the gods Osiris and Amun-Re. This is the papyrus where she is mentioned as the daughter of Hrere.

Her Mummy

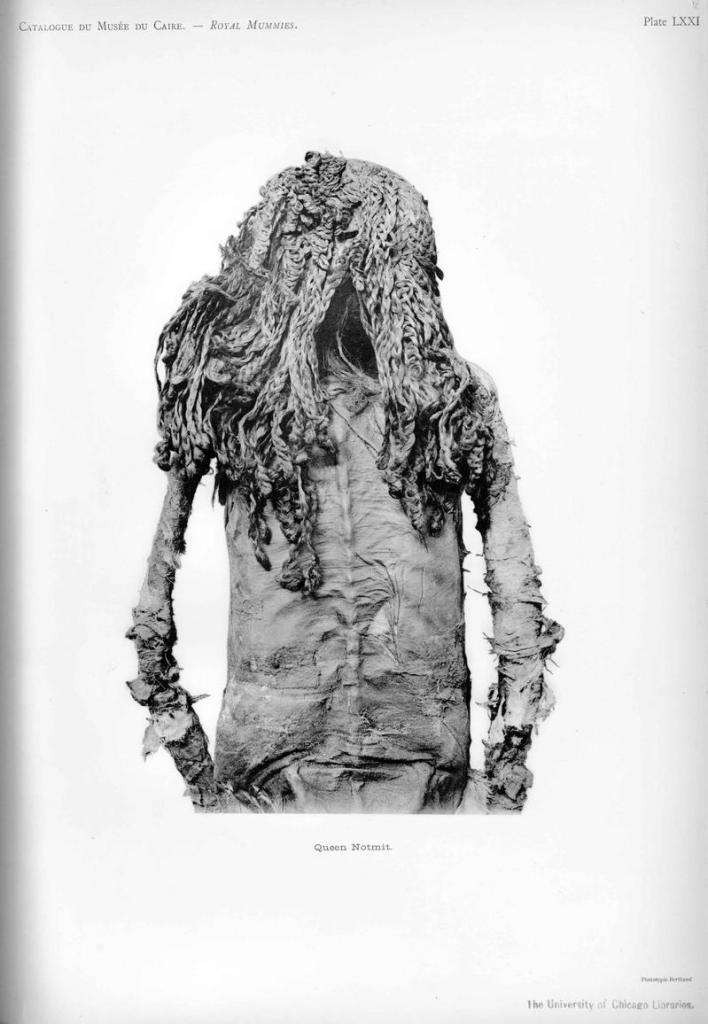

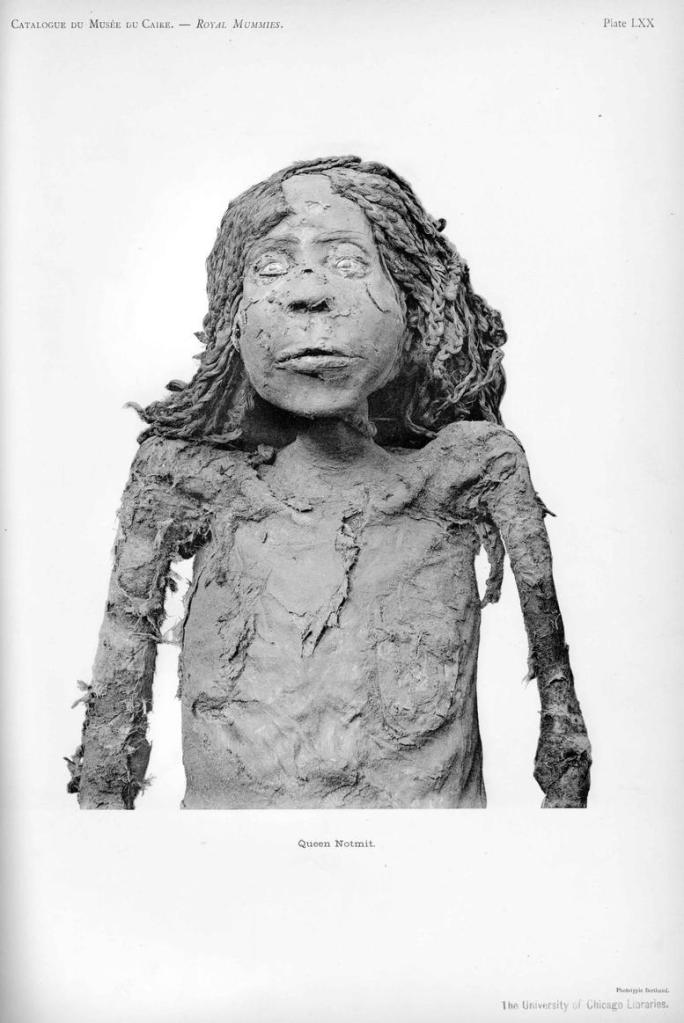

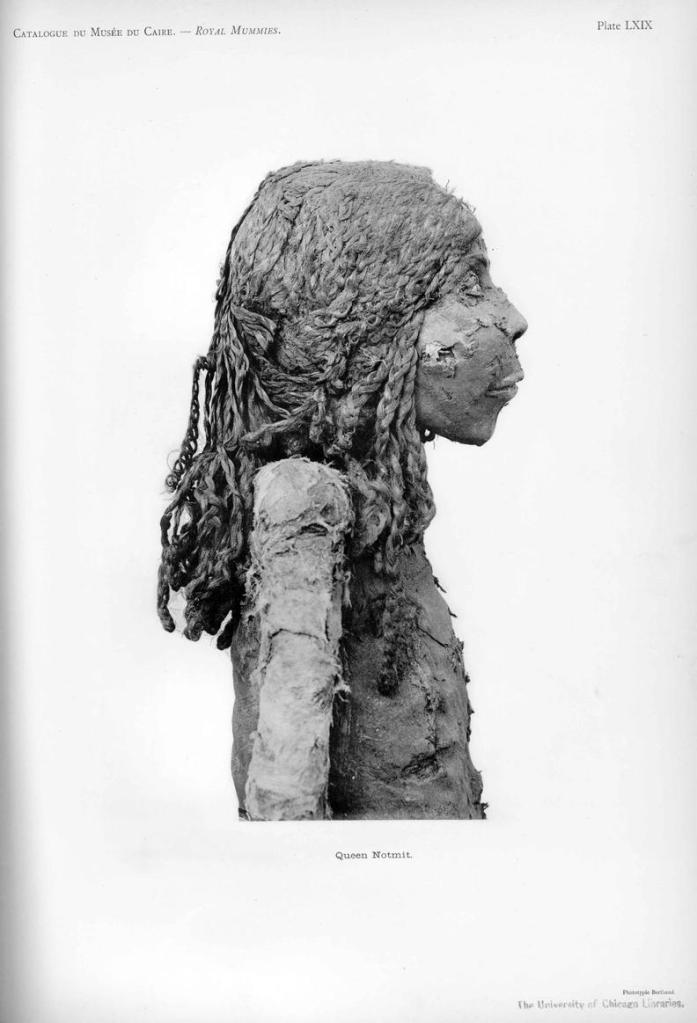

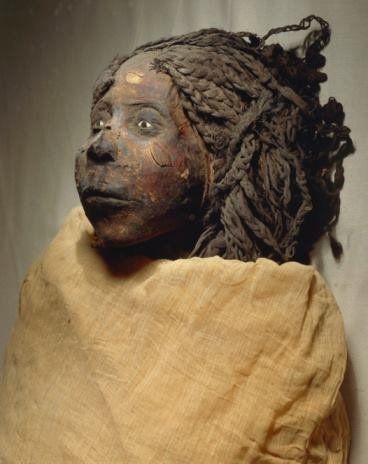

The mummy, currently located at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (CG 61087) was probably found in side room D of the tomb. The mummy was first unwrapped by Gaston Maspero on June 1st, 1886. G.E. Smith continued the unwrapping but only removed the remaining wrapping from areas of the body that were of special relevance to his study of ancient Egyptian embalming practices.

Some reports state that she was between 30 to 35 years old, while others claim she was an older woman. The mummy was in pretty bad shape after being presumably looted in antiquity. There were gashes on her forehead, cheeks, and nose, which were probably caused by thieves cutting the wrappings. Her legs, wrists, and left humerus were all badly broken. Impressions of jewelry were found on her right arm indicating that they had found and stolen some of the objects. But, several pieces were still found including several bracelets composed of tiny carnelian beads carved into the shapes of spheres and lotus buds, lapis lazuli beads, and gold cylinders.

X-rays of her body reveal that there was a heart scarab placed inside her chest, along with the figures of the four sons of Horus. Her viscera were not reinserted within the body like in late 21st Dynasty mummies, so it was probably placed in canopic jars which are now missing. The Osiris shroud that was covering her mummy was also damaged by looters. She was also reportedly found with an Osiris figure and a wooden canopic box.

Her original burial probably occurred around Year 1 of pharaoh Smendes, possibly in the tomb of Inhapi, the location of which is unknown. She was then probably reburied in TT320 after Year 11 of Pharaoh Shoshenq I. Three linen labels or dockets were found over the body. The first was found on the bandages on the sole of her foot and stated “High Priestess of Amon.” The second was found on the bandages on the right side of the body with her name written in a cartouche. The final docket had the date Year 1 of Smedes/Pinudjem I.

This mummy is also one of the first examples of a new mummifying technique. There was no attempt to insert materials under the skin via incisions, as was in the care of the later 21st dynasty mummies. The embalmers applied padding, wax, and other cosmetics directly to the surface of the skin to give the mummy a more lifelike appearance. To fill in her face, her mouth was packed with sawdust and her nose filled with resin. Artificial eyebrows made out of hair were attached to her face with some type of adhesive, probably resin. A wig was added on her head, which conceals a few remaining gray hairs. And finally, artificial eyes were placed within her eye sockets. This is the earliest known use of artificial eyes made of stone.

Even though we aren’t exactly sure which Nodjmet this mummy is, she represents a unique period of time where the power of the pharaohs was declining and mummification practices became more experimental.

Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nodjmet

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/DB320

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herihor

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Piankh

http://anubis4_2000.tripod.com/mummypages1/21A.htm

http://anubis4_2000.tripod.com/mummypages1/DB320Coffins/NodjmetsCoffin.htm

http://ib205.tripod.com/nodjmet.html

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/Y_EA10541

Photo Credits

Color photo of mummies, canopic box – http://anubis4_2000.tripod.com/mummypages1/21A.htm

Photos of Coffins – http://anubis4_2000.tripod.com/mummypages1/DB320Coffins/NodjmetsCoffin.htm

More Photos of the Coffins (NEED TO DOWNLOAD) – https://www.flickr.com/search/?q=Nodjmet&w=64758930@N00

Full length photos of the mummy – http://www.eternalegypt.org/EternalEgyptWebsiteWeb/HomeServlet?ee_website_action_key=action.display.element&story_id=&module_id=&language_id=1&element_id=66099&text=text

Photos of Papyrus (10541 – really pretty one) – British Museum

Photos of Papyrus (10490,1 ,2 ,3 ,4 ,5) – British Museum

Location of tomb – Ancient Origins

Isometric view of tomb – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3kyLTX0bmc8

View of shaft, other mummies – https://alchetron.com/DB320

3 comments